The Complete History of Role-Playing Games (RPGs): Part 4 – Here Comes the JRPG

Ever wondered where the idea of character levels or XP came from? Why is fantasy final? What RPGs looked like before graphics, or what the first massively multiplayer games were like to play? Here at Ultimate Gaming Paradise, we’ve got all those answers and much more in our series, delving into the history of role-playing games.

Enter the Japanese!

Episode Four: Here Comes the JRPG

Though the term itself was many years from becoming common parlance, the mid-80s were the explosive birth of the Japanese Role-Playing Game—or JRPG. With colourful graphics, emotive character-driven storylines and action elements, they lay the foundation of much that follows.

But before we discuss JRPGs, we first need to take a step back to 1981 and look at some ways game developers were working on bringing graphics to the genre.

Ultimate Wizardry

In the beginning there were two!

And they were Wizardry, and Ultima.

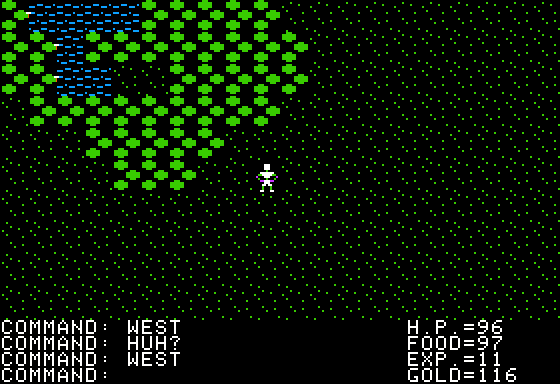

Developed independently, both Wizardry (Sir-Tech, 1981) and Ultima (Origin Systems, 1981) were games for the Apple II. They tried to find a different way to represent role-playing and breach that gap between Dungeons and Dragons and computer gaming. To be fair, they both did very well.

Unlike the ASCII-based Roguelikes, these made use of the Apple II’s ability to draw lines and basic polygons. Features previously developed primarily for accounting purposes and mathematical graphs were easily redeployed as dungeon walls, and complex mazes could become a reality. Add to that some pretty nifty colourful graphics for backgrounds, monster pictures and more, and these early titles seemed pretty groundbreaking.

Which, they were.

The draw and enthusiasm that players had for these games could not be mistaken, but it wasn’t just in America and Europe where their influence was felt. Over in Japan, the two games started to make an impression.

Passing Obstacles

Loving the American-centric, English-language role playing concept in Japan in the early 1980s must have been a labour of love.

Looming over everything was the language barrier. Written text is a key component of any role-playing game. With the source material only available in English meant that many Japanese enthusiasts had to be willing to dive into a different language just to experience the games at all.

Though only 40 years ago, this was a time before the internet and the widespread culture of international filmmaking. Of course, both TV and films from the west were circulating in Japan, but English wasn’t the familiar language it is today. Even now, in 2021, only 30% of Japanese have a basic understanding of the language (with only between 2% and 8% in any way fluent). During the early 80s, that number was significantly lower.

Games didn’t have regional translations—Dungeons and Dragons itself didn’t have an official Japanese printing until 1985—so games like Ultima and Wizardry had an uphill climb to reach any sort of user base.

Despite that, Wizardry stormed Japan, becoming one of the highest-selling games of the time, and far surpassing its Western fanbase. When a native-language Japanese version of the game The Black Onyx came out in 1984, it opened the floodgates.

The Magical and Mythical Triumvirate

The Legend of Zelda.

Dragon Quest.

Final Fantasy.

These three games have managed to influence the world of role-playing games in such a significant way that it is impossible to even imagine an RPG today that doesn’t list them in its influences. One of these three behemoth series for so many gamers was their introduction to the genre, and it probably remains their favourite and most beloved.

They are the dawn of the JRPG.

The Legend of Zelda – Mixing Action with Role Playing

Of the three, technically, The Legend of Zelda was first. With a release date of 21st February 1986, it pips Dragon Quest to the post by eight months and is a full two and a half years before Final Fantasy.

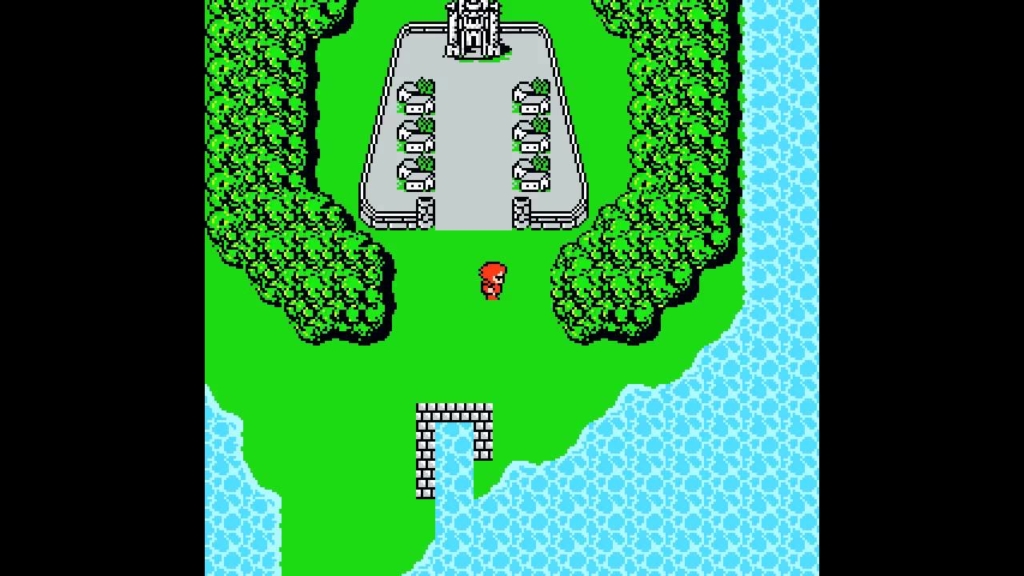

Developed by Nintendo for their Famicom system, released worldwide as the NES, The Legend of Zelda was inspired by game super-legend Shigeru Miyamoto’s childhood trip into a cave with only a lantern to light his way. Spurred on by the success of games like Wizardry and Ultima on the Apple II, he and fellow developer Takashi Tezuka were determined to bring some of that excitement to the console.

Miyamoto was no rookie game designer, though. Neither did he come from Dungeons and Dragons‘ background, simply wanting to replicate his experience of tabletop role-playing onto the game screen. Rather, he was the up-and-coming star of Nintendo, the man who brought us Mario, and he knew very well what it was to make a game.

One of the qualities missing from many early attempts at a role-playing game was the focus on fun. Bogged down in statistics and the desire to get as much role-playing into the experience as possible, the designers often lost sight of the main impetus that drove them—to enjoy themselves. There’s no doubt that Ultima and Wizardry and everything else coming out at the time were mainly fun but, sometimes there were long stretches of not-fun that accompanied it. The player’s determination to enjoy themselves overrode this small failure and meant they would persevere.

Not so when Nintendo’s developers sat down to make The Legend of Zelda. From the outset, it is easy to see that they were coming at it with their game-experience at the forefront, with the role-playing part a clear secondary concern.

How can you tell? Play the very first Zelda game today, and it feels like an arcade game. Each area is like a separate room, where you stab at baddies using a real-time action. Yes, statistics are running the game in the background, calculating damage and health, but the user experience is closer to PacMan than Dungeons and Dragons.

And it works.

The numbers part of role-playing, all those character stats and charts, dice rolling and luck, all of it is really something we (as players) would rather not be dealing with. Isn’t that the point of using a computer in the first place? To help immerse us in a world of imagination and fantasy without worrying if a sword will hit for five damage points or six? By removing the bulk of the numbers from the player and concentrating on the game experience, The Legend of Zelda allowed players to get engrossed in a different way, with story and skill rising to the top of the pack.

The Legend of Zelda didn’t even have experience points!

Dragon Quest – A Whole New World of Adventure

Just before Christmas 1986, Dragon Quest launched, and the JPRG as we know it today was born. While The Legend of Zelda had its own take on what parts of the role-playing experience it did or did not want for a successful game, Dragon Quest went all in.

It took from Ultima and Wizardry like a leech, stealing every good idea and claiming them as its own. Then it added a sense of the cartoony and a real feel for story and world-building and layered it all over the top, creating something that has become one of the most successful role-playing series of all time.

For players in 1986, Dragon Quest (called Dragon Warrior on the American NES) was a real eye-opener. Full-colour graphics and a real sense of progression as you followed the story through countless text boxes of written speech.

And then there was the combat. One of the draws to role-playing games for so many players is that lovely sense of growing your character, gaining in experience points and unlocking new abilities, new spells, and greater and greater damage-dealing strikes as you go on. Monsters that caused you trouble early in the game are despatched with a single swing of your sword later on, and you get closer and closer to being strong enough to defeat the end game bad guy, an adversary so impressive that they have been the subject of the storyline from the very beginning. An ultimate foe—the Dragonlord.

Final Fantasy – The Beginning of World Domination

If The Legend of Zelda and Dragon Quest opened a door. Two years later, Final Fantasy stuck a great big wedge in it make sure that door would never shut.

Designer Hironobu Sakaguchi was ready to throw in the towel concerning designing games but was determined to make an RPG. When the project was green-lit, this game, the last one he ever planned to make, became his ‘final’ fantasy.

Of course, success has a way of changing minds, and Final Fantasy I spawned a number of sequels that made the name a bit of a misnomer.

Inspired again by Wizardry, but with Dragon Quest to also look at, the development team at Square sought to fix everything that was missing from their rivals and to develop a deeper, more engaging role-playing system.

Multiple characters in classes of your choice, monsters that are vulnerable to certain elements and weapon types, vehicles to allow transport to different areas, and an easy-to-understand battle system were all a good start. But, it was in world-building where Final Fantasy truly made its mark.

With a strong focus on art and music, using the amazing concept-art designed by Yoshitaka Amano and in-game tunes developed by Nobuo Uematsu, the Final Fantasy series was the first to really start to look at the idea of a computer role-playing game as an entire experience. Players were quickly embroiled in the story, fixated on improving their characters, and humming the catchy tunes (even limited by the sound output of an NES) as they went about their day.

Final Fantasy wasn’t just a game, it was an obsession.

It’s not All NES

While it is true that the Nintendo Entertainment System was the main platform for these new Japanese role-playing games in the middle 1980s, it did have one rival—the Sega Master System. In the days before the Megadrive (Genesis to our US readers), the Sega Master System had managed to position itself in a few markets to fight Nintendo. One of these markets was the UK, where the Master System did quite well.

Not wanting to be left out in the cold when it came to the new wave of role-playing games, Sega developed Phantasy Star—another title in the mould of Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy that collected its fair share of devotees. With a nod towards sci-fi, Phantasy Star also managed to find a niche for itself, proving that content didn’t need to be all wizards and dragons.

Phantasy Star was another success—with a series of sequels still in existence today—proving that Nintendo weren’t the only people with a machine capable of playing these awesome games.

Hitting the International Market

With Nintendo’s worldwide marketing power, these role-playing games weren’t limited to the Japanese audience. They rolled their way around the globe and found themselves translated into English, appearing on screens everywhere. Many who played them couldn’t imagine how they could be improved, feeling that computer and console gaming had peaked.

Of course, the gaming community split. There were plenty who were willing to reject these eastern usurpers, preferring to remain loyal to the development of western role-playing games that had a somewhat more serious, less cartoony feel to them. However, even they couldn’t deny that by the tail end of the 1980s, the JRPG had very much arrived.

Coming next…

What was happening in the rest of the world while Japan was busy kickstarting series that would go on to shape RPG gaming well into the next century? Well, there was a bard… and he had a tale to tell…