History of the Game Engine: Part 3 – The Rise of 3D Graphics

As we have seen in previous parts of our History of the Game Engine series, the 1990s was a momentous decade for gaming and probably the one that was pivotal in so many ways. Systems like the Super Nintendo, Sega Genesis, N64, and PlayStation created scores of devoted new fans and sparked the beginning of console wars that rage on even today. But how did the graphical features of gaming come to what we know today? What is the story of 3D graphics?

Gaming started to become serious in the 1990s, and console manufacturers and game developers started to notice what a massive market this could be. It was the decade when people actually rented games (no, really) and phoned up developer-run ‘tip lines’ when they couldn’t work out a level for themselves. It was when saving a game meant taking up precious space on your console, or you had to buy a memory card, and you sometimes had to flip your PlayStation upside down to get the CD reader to scan a game disc properly. It was definitely odd times (though we thought it was normal), but the ’90s was also the decade when developers started to really get to grip with the holy grail of gaming; 3D graphics.

Popular Products

The modern videogame arcade was birthed in the 1970s. The first arcade games used real-time 2D sprite graphics, but this was also the decade in which developers started to consider 3D graphics. Computing power was growing, albeit quite slowly. Moore’s Law—the notion that transistor numbers on a dense integrated circuit would double every two years—was holding true, and the ability of computers to do more was growing with it. There was a growing possibility that graphics could be driven by dedicated cards and could push more detail and even true 3D imagery.

In descriptive terms, 3D computer graphics use a three-dimensional or cartesian representation of geometric data. A 3D image or character appears to have height, width, and depth are three-dimensional, while an image or picture with height and width but no depth is referred to as two-dimensional or 2D.

A potted history of 3D in Gaming

Initially developed by Steve Colley, Greg Thompson, and Howard Palmer for the Imlac PDS-1 computer, Maze War is regarded as one of the earliest entries in 3D graphics and a driving force behind what would eventually become First Person Shooters (FPS). Simple in its construction, Maze War allowed a player—pictured as a large ball—to navigate a block-based maze and shoot other players in a monochrome vector display, continually refreshed from the computer systems local memory. The basic controls let the player move forward, back, left and right only. The addition of height in the graphics gave the player a feeling of three-dimensional play, even though they were effectively rooted to the ground.

Initially, the game only offered a simple representation of 3D graphics but soon became a tad dull as the user worked their way around an endless maze. One of the developers then had the idea of adding the graphics that included a stylised gun, coding in collision physics, and connecting two systems via their serial ports. Suddenly, two players could hunt each other around the maze, and the concept of the FPS came into being.

Also vying for the position of the first 3D game was Spasim. Spasim was similar in its physics and design to Maze Wars and allowed up to 32 players to fly around the defined area and interact. Driven over the PLATO (Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operations) system—remember, the internet was still just a twinkle in Tim Berners-Lee’s eye—Spasim captured the imagination of those who were lucky enough to play it.

The initial release of Spasim inspired the developers of Empire to use much of the game’s code to develop the flight simulator game Airace in 1975—also coded for the PLATO system. This led to the creation of Airfight, another flight simulator, and then the tank driving game Panther later on in the same year. All these titles were based on the same kind of graphics and running on the PLATO platform.

The Spasim game has also been cited as a “spiritual ancestor” of Elite (circa 1984) and the long line of space trading games that sprouted from it. So, not only was Spasim one of the first 3D games around, but there is also direct evidence that it was the first game in which sections of its code were shared to produce another title. As such… making it the great, great granddaddy of the game engine. You know, the thing that we are looking at overall in this series!

The 1980s saw the rise of so-called pseudo-3D graphics. With these, game programmers would use physical, graphical projections to give the illusion of 3D or use basic 3D gaming environments limited to a 2D plane to give the same effect. In this way, the gameplay is restricted to a two-dimensional plane with little to no access to the third dimension in an environment that appears to be three-dimensional. This became known as a 2.5D system. You, as the player, could only move forward, back, left and right on the X and Y axis, but the world around you existed above and below you on the Z-axis. A very different experience to the side-scrollers and top-down shooters of the past.

Fresh In

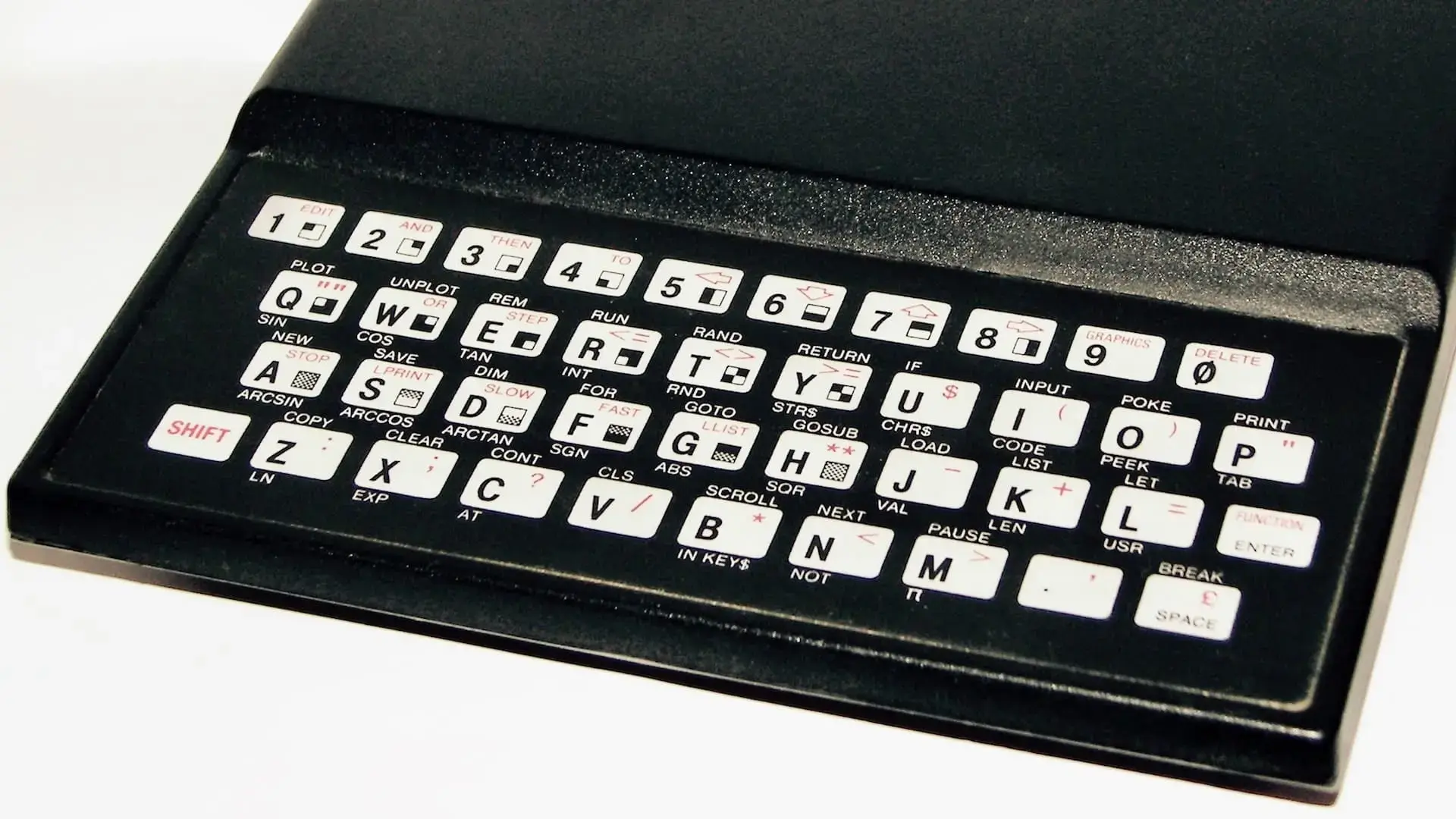

The first home computer 2.5D game to be released was 3D Monster Maze in 1981, which ran on the ZX81. The game was a little light on entertainment (and frights) as a blocky and badly drawn Tyrannosaurus chased you around a randomly generated maze. Despite being low-rent graphics, 3D Monster Maze quickly made the ZX81 overheat. This lead to all manner of insane faults such as randomly-appearing walls and only half a monster to chase you around. The only solution was to turn it off and let the system cool down while you had your tea before restarting. Luckily, there was no real point to the game apart from evading the snapping monster, so you could start it anywhere and not miss out on too much.

The 2.5D system actually survived for some time.

It is difficult to discuss 3D gaming without mentioning the great John Romero and his collaboration with John Carmack, which resulted in PCs becoming as game-friendly as purpose-built consoles—and drove the big push for true 3D graphics. But if we are going to discuss Romero and Carmack, we need to give a nod to Dylan Cuthbert.

As programmers, PC users and game aficionados, one of Romero & Carmack’s main issues was the fact that side-scrolling wouldn’t work on PCs as it did on consoles, and that was a big problem. With a PC, rather than being a smooth transition through the game, the backdrop tended to move as a block when the player sprite got to the edge of the screen. The team had developed an Apple II and MS-DOS-based example title called Dangerous Dave. Carmack was convinced that he could meld Dave with Nintendo’s Mario architecture and get the best of both worlds on a PC. He set about doing it. Carmack got to work “hacking” a Nintendo and found the actual work easier than expected. Soon, he had a Dave/Mario hybrid complete with effortless side-scrolling. While the game wasn’t saleable, it demonstrated that there was code available – though snatched from Mario – that could make PCs as seamless as a dedicated games console. That was a big deal and potentially a huge leap in technology.

Popular Products

As a result of this technological advance, Romero and Cormack decided to start a new gaming company. On February 1, 1991, id Software was founded—dedicated to improving upon the graphics of games in general, but on the PC in particular. At this time, consoles (and jacked PCs) still only played out games in two dimensions; the player could move left or right and jump up or down, but that was a constraint. Romero and Cormack were determined to change that.

So where does Dylan Cuthbert fit into all this?

While Romero and Carmack were busy hacking Nintendo and solving side-scrolling, a young game designer in London called Dylan Cuthbert was working with Argonaut Software on the problem of 3D graphics. The company wanted to make a 3D game for the Nintendo Gameboy, but the intellectual property (IP) issues allowed only companies with Nintendo’s blessing to do that. Cuthbert and Argonaut didn’t have that, so they did the very next best thing; they tore a recently-purchased Gameboy to pieces to see what made it tick! Having reduced the assembly to its components and laboriously identified the pin-outs and functions, they set about altering it.

Figuring out which pins did what allowed Cuthbert to hack into the main chips and install different data. With the possibility of fundamentally altering the programming of the Gameboy, Cuthbert and Argonaut set about writing their own game for the system. Initially figuring out how to code in a wire-frame based space-flight game, Cuthbert installed it on the hacked Gameboy; voilà, the first rudimentary 3D game on a Gameboy!

Now, this could have meant a whole heap of trouble, particularly when someone at Nintendo saw the prototype. However, rather than threaten Argonaut with all sorts of legal nastiness, the Japanese company were intrigued—sufficiently so to fly Cuthbert and his colleagues over to Japan. In the midst of a huge, formal meeting, Nintendo cooed over Cuthbert’s modifications and expressed interest in making the 3D space game an official Nintendo release – kerching!

But there’s more too! During the meeting, the chief designer from Nintendo presented the companies latest handheld console design. Nintendo wanted to develop 3D games and asked Cuthbert if he could assist them with the project!!! From any game designers’ point of view, heaven didn’t get closer than this!!!

However, there was a problem. The new console’s design was all but sealed in terms of hardware and space envelope and couldn’t handle 3D graphics. The Nintendo boys wondered if Cuthbert could weave some of the magic he had used with the Gameboy. Basically, Nintendo asked Cuthbert to hack the console and do something extraordinary to get 3D out of it.

Cuthbert pored over the console, took it to pieces, examined wiring diagrams, checked pin-outs and ports, and imagined the unimaginable… finally declaring that he couldn’t get the hardware in the console to drive 3D.

Just as the Japanese designers’ faces fell, Cuthbert proposed something else, something new—he proposed putting the 3D driver hardware inside the game cartridge itself! Rather than having the 3D graphics driver built into the new console, the driving chip was part of the game cartridge architecture. This, then, became the Super Effects chip and helped Nintendo become the gaming power of the last part of the 20th century. It can also be classed as one of, if not the very first, examples of a piece of hardware dedicated to rendering graphics. Or more commonly known today… a graphics card.

Cuthbert and Nintendo had created a 3D space-flying game, but the Chief Designer, Shigeru Miyamoto, was concerned. The game allowed the player to navigate in any direction, and it was thought to be confusing. To give the 3D open-world some structure, Miyamoto came up with a concept where the player had to negotiate the craft through a series of gates. Inspired, it is said, by the many gates of the Inari Ōkami shrine to which Miyamoto was a frequent visitor. Star Fox was born.

The development of the game required a lot of input, and Cuthbert engaged the help of English programmer Giles Goddard to help create the physics and the aesthetics of the title. In doing so, they developed a lot of fundamentals that became sacrosanct within 3D games, and 3D flying games in particular. They had to work out the best place for the camera; if it were locked in place behind the player’s spacecraft, then the feeling of 3D movement would be lost, and it wouldn’t feel like the Arwing plane was turning, and if it were static with the craft moving around the screen, it would become confusing. As a result, the team instigated a lag between the movement of the Arwing and the camera. This accentuated the feeling of actually moving in 3D.

Popular Products

Playing on the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (rather snappily known as the SNES), and with the 3D Super FX chip on the game cartridge, Star Fox was relatively fast, fun to play, worked well as a 3D game and went on to be a huge success for Nintendo.

Back in the United States, Romero and Cormack, thrilled by their ability to hack the Nintendo software, were pressing ahead with their own 3D aspirations. Using previous bits of code that they had, ahem… come across, alongside new code that they had created, they were fast creating their own 3D environments for the PC. In 1992, they transformed their smooth side-scrolling premise and turned it into a forward scrolling concept. They showed this off with a new title, called Wolfenstein 3D!

The 3D texture-mapped shooter captured the gaming public’s imagination and set in motion id’s rise to becoming a major star in the gaming industry. But more than just being a 3D game, Wolfenstein 3D was played at 70 frames per second (FPS), with full-colour rendering and digital sound. Compared to the opposition, it was revolutionary. It wasn’t much later that Romero & Carmack released a true 3D title in the form of DOOM!—a story you can read about here.

These two unconnected incidents are at the root of today’s 3D gaming. Without either, games wouldn’t be anything like they are.

Rise of the Fifth Generation Game Consoles

Towards the end of the 90s, the launch of so-called fifth-generation gaming consoles marked the turning point towards real-3D games. Fifth-generation consoles were also known as the 32-bit era, the 64-bit era, or the 3D era, refers to computer and video games, video game consoles, and handheld gaming consoles dating from 1993 to 2006. The fifth-generation systems included a number of defining features, geared toward true 3D gaming, including:

- 3D polygon graphics with texture mapping.

- 3D graphics capabilities – such as lighting, Gouraud shading, anti-aliasing and texture filtering.

- CD-ROM game storage, which allowed much larger storage space (up to 650 MB – woohoo!!) than ROM cartridges, and sped up game content access.

- CD-quality audio recordings for both music and in-game speech, featuring PCM audio with 16-bit depth and 44.1 kHz sampling rate.

- The widespread adoption of full-motion video, displaying pre-rendered computer animation or live-action footage.

- Display resolutions ranging from 480i/480p to 576i, with a typical Colour depth up to 16,777,216 colours and 24-bit true colour.

With the advent of games such as SuperMario 64 and Sonic Adventure, almost all video games were geared towards the 3D market that only FPSs and driving games had attempted before. This change was met with technological advancements, particularly switching from cartridge to disc in the home console market. This allowed for much larger, fully 3D worlds that were to come a few years later.

3D Gaming – The Legacy

The rise of 3D graphics in gaming is a huge subject, filled with tales of hardware upgrades, software that was now being shared—for a price—amongst different developers, and a drive to make gaming more realistic. Once developers saw what was possible, it became a contest to produce games that could match the hardware, while hardware manufacturers constantly tinkered to get more power out of their consoles. One drove the other in a race to make games more realistic, and with the market value of the industry skyrocketing, there were handsome financial rewards to be had.

Fresh In

Nowadays, we’re used to seeing incredibly life-like characters populating our screens in worlds that have realistic structures and even plausible weather systems. We look in on worlds that are so realistic that we are drawn into them. VR is now taking 3D two steps further with immersive worlds that are increasingly believable, and our hardware is keeping pace with the developments in software. It is, undeniably, sunny times ahead for the gaming community.

Next time, we’ll delve into the world of Role-Playing Games and how they, too, fuelled the rise of game engines and cross-pollination between developers.