The Great Chip Shortage of 2020 – 2021

And it’s Likely to Continue for Much Longer

Last week, while I waited to collect a cordless drill from a Currys PC World in north London, a man ran into the store, pushed in front of me and slapped his hands on the counter. He looked like he had been running for some time. It was clear that something was troubling him.

“I need a PS5”, he panted. He had not ordered one and there were none in stock, which may come as no surprise to anybody. The store assistant explained that there were problems in the supply chain. The customer didn’t want to hear it. As far as he was concerned, it was the store’s fault for not ordering enough consoles, and the assistant was now getting the brunt of his ire.

She tried to reason with the man, but his voice got louder. “My friend’s son told me they’d be here!”

Another member of staff came to the scene to explain the chip shortage, but he refused to believe him as well.

As security calmly led him away, I wondered which rock this poor soul had been hiding under. I collected my drill.

News of the semiconductor shortage may have bypassed our man in Currys, but anyone who has tried to bag the latest consoles and graphics cards will know the frustration.

Since it was released in November 2020, the PS5 has remained particularly elusive, as has the Xbox series X and S, and nearly all graphics cards. Cryptominers are largely to blame for the GPU shortage, while scalpers have used bots to decimate stock to resell on eBay for triple the original price.

Threads on Reddit surfaced with updates on the availability of PS5s and Xbox series X and S. One user wrote:

“My plan is to stay up until about 12.30 am Thursday in case anything becomes available from midnight.

Then I am up at 5.30 am for work where intend to [do] nothing but press refresh for 8 hours.”

Another wrote:

“Not even gonna go into full detail. You all know the song and dance. Been up since 6 am for this s*** after going to bed at 2. Literally hit the page as soon as it went up. It went into my cart. And then after trying to finish the purchase it ***ing took it out of my cart for God knows what reason, and I couldn’t add it back in because it was sold out in my area. I’m just so done man.”

The shortage seems no sign of alleviating any time soon. Interviewed by Bloomberg, Toshiba chip specialist Takeshi Kamebuchi said: “The supply of chips will remain very tight until at least September next year. In some cases, we may find some customers not being fully served until 2023.”

Can’t We Just Make More Chips?

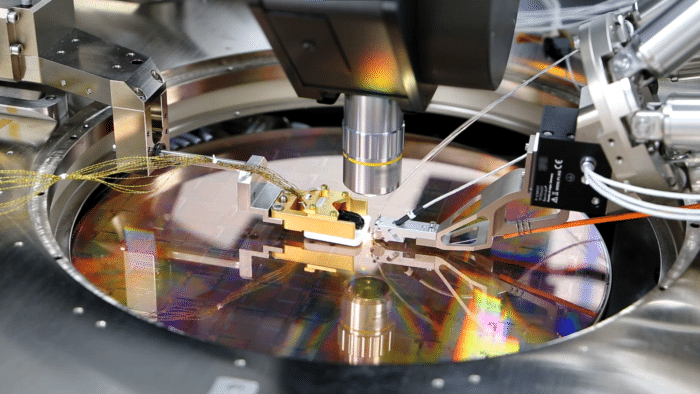

No. One chip takes at least three months to manufacture and is produced in a semiconductor fabrication plant (or fab, or foundry) that takes years to build and billions of dollars. And there aren’t enough fabs to go around, because the state-of-the-art foundries needed to make the chips for consoles and cars have not yet been built.

It starts with sand. For advanced chips, you want some fine white sand that can only be found in the Appalachians in North Carolina. The sand is converted into silicon in a furnace within a fab. The fabs are highly controlled, air-filtered, dust-free space thousands of times more sanitary than an operating theatre, where technicians wear coroner-style suits. The silicon is rarely if ever handled by humans. There are billions of atom-sized transistors printed onto one chip. Divided into wafers, it undergoes hundreds of steps and tests before it is ready to be shipped to electronics manufacturers globally for use in every piece of technology that exists.

Where is Our Tech?

The chip shortage has wreaked havoc on the availability of advanced electronics. The COVID-19 pandemic has affected every step of the supply chain, from production to testing to transportation, while a global lifestyle change has increased demand exponentially.

There was a surge in demand for new PCs as workers transformed their homes into offices. Others adopted digital technology as a way to communicate with others. But the new interest in home entertainment was unprecedented: in particular, video gaming. Figures from UK industry body Ukie found that Britons spent £7bn on video games and equipment in 2020 – up from £1.6bn the previous year.

The new uptake would have impacted the semiconductor industry without the further complications of the pandemic.

Taiwan faced its worst drought in 50 years, which may have affected production. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing (TSMC) is the largest contract chipmaker in the world, making chips for Apple, AMD and Qualcomm, among others. The country relies heavily on seasonal typhoons for water, and fabs need a lot of water. They pulled resources from the south of the country where there was more rainfall, and although the company said production wasn’t affected by the drought, news reports suggest otherwise.

TSMC was also affected by COVID-19 outbreaks but again said this did not impact manufacturing.

While silicon mining was largely unaffected, borders were closed and factories were shut down, either because they were considered non-essential, or because workers had contracted the virus. In March 2021, there was a fire at the Renesas Electronics foundry in Naka, Japan. Manufacturing machines used to make chips for Nintendo consoles were destroyed and the foundry ceased production for more than three months. Samsung’s S2 fab in Texas also closed at a cost of $270m after a storm in Austin left 200,000 homes without power.

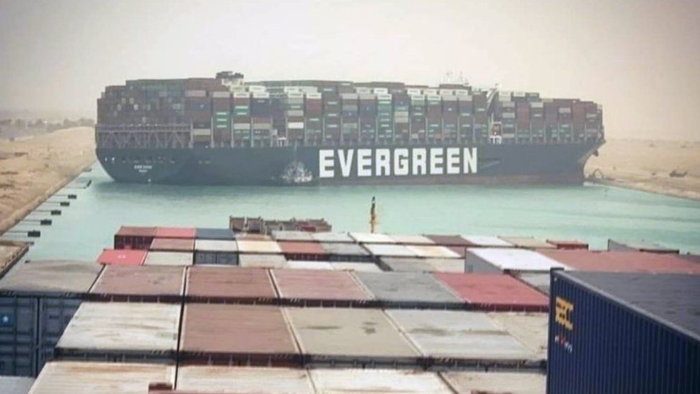

And remember that ship stuck in the Panama Canal? While the Ever Given Evergreen cargo vessel – one of the largest in the world – was wedged between its banks, it created a traffic jam of 360 ships and cost billions in delayed shipments.

Many of these issues are ongoing.

In June this year, a semiconductor testing site, King Yuan Electronics Co (KYEC) temporarily closed its doors as 182 employees tested positive for COVID-19. Following that, a severe COVID-19 outbreak at Malaysian chipmaker Unisem caused the death of three people and meant the fab closed for a week from 9th September.

Toyota announced temporary shutdowns at factories worldwide, cutting production by 40% in September.

In August this year, unconfirmed reports that Malaysian company STMicroelectronics has closed after an outbreak of the virus. The country, which operates more than 50 semiconductor production foundries, recently imposed its fourth lockdown due to a rise in daily COVID-19 cases.

Further effects of the Covid-19 pandemic include the rise in shipping costs from Asia. A spokesperson from Logistics UK told the BBC that prices have risen by up to 800% — up to £7,820 for a 20ft container. This compares to £870 for the same container pre-COVID-19.

The Fallout

The shortage has not just been rough on gamers. Smartphones, cars and Internet of Things devices have been similarly affected.

In 2020, Apple delayed the release of the iPhone 12 by two months, with a three-week waiting time on top of that. To drive home in Tesla’s more expensive models – the Model X and the Model S – you’ll have to wait until around April 2022. Some Jaguar Land Rover designs emerge after a 12-month waiting time.

Other carmakers, eager to claw back lost sales, are leaving out high-end features on new models. Peugeot has replaced its digital speedometers with plain old analogue ones, and Nissan has temporarily scrapped the navigation system from thousands of vehicles. In some versions of Ram’s 1500 series pickup truck, there is no intelligent rear-view mirror.

Daimler CEO Ola Källenius said he expects the chip shortage to continue into 2022, possibly 2023.

The Scourge of Scalpers

While the pandemic forces fabs to cease production, scalpers are taking advantage of the shortfall in GPUs. The notoriously difficult-to-find NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 can be bought on eBay for triple its original price. With the help of bots, scalpers don’t need to touch their computers because an automated programme will check availability every three seconds and buys up every GPU it can.

The Rise of Bitcoin and New Demand for Graphics Cards

As the price of Bitcoin and Ethereum erupted, cryptominers stashed hordes of graphics cards to cash in on the trend. Miners need graphics cards to crack the Proof of Work (PoW) system. PoW is a complicated calculation that proves transactions across the network are authentic. But to crack the puzzle, miners need huge amounts of energy (the equivalent of Norway’s national usage) to surge through the GPU. And this ultimately shortens the life of a graphics card. Miners can easily repackage graphics cards and sell them off, labelled as new, at exorbitant prices.

Attempts were made to limit the capabilities of graphics cards for mining purposes, but so far this has had little effect on the stock shortage. In February 2021, NVIDIA announced that were limiting the hash rate of GeForce RTX 3060 GPUs to make them less desirable to miners. At the same time, the company released a graphics card specific to mining.

In May, they took additional measures to get their GPUs away from the hands of miners, by applying reduced hash rates to new models GeForce RTX 3080, RTX 3070 and RTX 3060.

But there is good news. The PoW system is set to be usurped by Proof of Stake (PoS), where miners have to prove their income in order to mine currency. There is no need for a GPU and it’s much better for the environment, which will make Elon Musk happy. The Tesla boss said he would start accepting Bitcoin again if the energy used to mine it was at least halved.

Ethereum is one currency to adopt the PoS system through a series of upgrades over the coming months to meet sustainability requirements. Following the proposed move, Ether’s price soared to over $3,000. It is believed the innovative transition will impact Blockchain itself. Blockdaemon CEO Konstantin Richter told Tearsheet that the upgrade is a “watershed moment for the crypto industry”.

Memory Loss

Of course, the chip shortage is not unique to 2020/21.

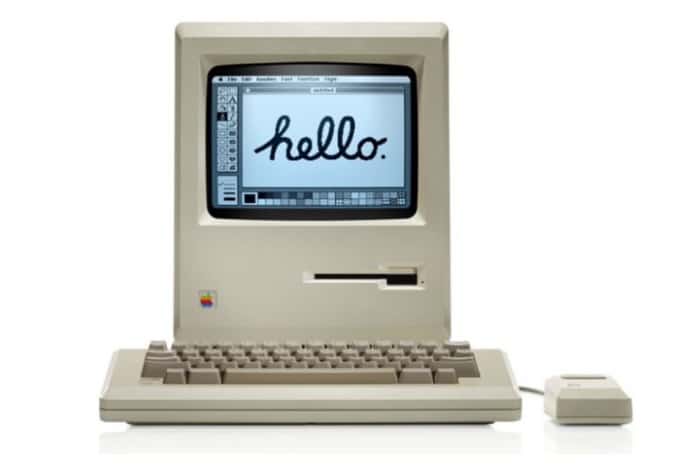

Scroll back to 1984: Steve Jobs launches Apple Macintosh (while you’re here, check out the now-ironic TV commercial from the same year). Millions of people become addicted to a new phenomenon called Tetris. DNA fingerprinting is discovered, which would, for one, revolutionise the criminal justice system. Computers were becoming a regular fixture in people’s homes.

Their most common use? Video games…shortly followed by homework.

Back then, most IBM computers held a whopping 64k of memory. But the unprecedented demand for new technology meant there weren’t enough dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) or static random-access memory (SRAM) chips to go around. To combat the famine, more fabs were built across the globe, many of which were in Japan. The availability of chips soared and prices dropped substantially.

Prices were pushed down not just because of the increase in supply, but because Japanese manufacturers were selling chips below the cost of production. This practice, known as dumping, is usually intended to capture the foreign markets to which they export, in this case, the US. In most circumstances, dumping is illegal.

By 1985, chips were selling fast and cheap. Around this time, there was an unexpected decrease in demand for computers, creating an abundance of chips. Chips were everywhere. So in 1986, under scrutiny from the US, the Japanese trade ministry instructed chip producers to limit their production and made manufacturing licences harder to come by in order to recuperate the US semiconductor market. But it was too late. As a result of the dumping, five major US companies had ceased production, leaving only Texas Instruments, Micron Technology and Motorola as the sole DRAM and SRAM manufacturers. And as demand for technology inevitably increased again, chips became scarce. This unintended consequence led to a huge increase in the price of semiconductors. By 1987, a chip that could be bought for $2 six months earlier, was now worth $12.

As electronics became more sophisticated, semiconductors needed more memory to cope. There weren’t enough chips to meet the speed at which technology was advancing and to sate the hunger of tech consumers.

In 1988, Final Fantasy II hit the market. Steve Jobs launched the Apple II Plus (a slight upgrade from its predecessor the Apple II) and graphic designers were being seduced by the very first version of Photoshop. The most popular 256k DRAMs were in short supply, and the demand for 1MB chips, which were more expensive and more complicated to produce, had increased. By trying to counteract the problem by building new fabs, we were now left with less than before — and the chips that were on the market were all but unaffordable.

The shortage was compared to the 1979 Oil Crisis. Computer sales were affected. Uncertainty led to Nintendo delaying the release of Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, while Super Mario Bros 2 was also pushed back. Some reporters, such as ABC’s John Stossel, questioned whether the chip shortage was a conspiracy dreamt up by Nintendo to increase sales. We can only imagine the hellish scenarios in Currys at Christmas 1988 when disgruntled gamers and parents tried to get their hands on the latest Zelda.

The chip market eventually recovered, but in 1994 it was in trouble once again as the ever-evolving industry needed to overhaul its foundries to produce more advanced tech. Sound familiar? Again in 2004, when mobile phones became ubiquitous, code-division multiple access (CDMA) chips, needed for their transmission properties, were hard to come by. And in 2010, there had been little investment in expansion due to fears of a double-dip recession, leading to Apple’s admission that they couldn’t make enough iPhones to satisfy demand.

The Future is… Expensive

Clearly, the solution is to make more chips, and quickly. We know it is not that simple, and now the price is expected to rise as manufacturers need to recuperate the cost of expansion.

South Korean chip manufacturer Samsung revealed its intent to expand its S5 facilities. Its most advanced foundry produces NVIDIA GPUs and Qualcomm Snapdragon 888 chips and the expansion is set to cost $26.3 billion. Senior Vice President of Samsung’s Investor Relations department, Ben Suh, announced that the company would adjust pricing to support growth. And TSMC has confirmed a price increase of 20% after pledging to invest $100bn in production. United Microelectronics are among others that have raised prices.

Chip and supply chain specialist Peter Hanbury, Partner at Bain & Co, predicts this price increase will continue and affect the end-user as production costs increase.

He told Nikkei Asia: “[For] products like smartphones and PCs, the price increases will be more noticeable, while for other devices with limited semiconductor content you may not even notice.”

The sad state of semiconductors has brought many gamers to the brink of despair, but we have to hold on to the knowledge that there’s an end in sight. Semiconductor companies worldwide are building new fabs. Intel plans to build two nanometre chip-producing fabs in the US. TSMC said it would build a $12bn foundry in Arizona, and Bosch is building one of the most advanced wafer fabs in the world.

Yes, your tech will initially cost a bit more. But nowhere near as much as the resale price of RTX 3080s on eBay. And as the pandemic causes havoc in just about every component of our lives, maybe we need a bit of perspective and a little patience.