The Complete History of Role-Playing Games (RPGs): Part 2 – The Adventure Game

Ever wondered where the idea of character levels or XP came from? Why is fantasy final? What RPGs looked like before graphics, or what the first massively multiplayer games were like to play? Here at Ultimate Gaming Paradise, we’ve got all those answers and much more in our series delving into the history of role-playing games. So, what did those first role-playing adventures look like?

Episode Two: The Adventure Game

Graphics are overrated, right? I mean, who needs all those fancy pictures taking up your headspace when you could use the power of imagination? Words, my friends, words!

Unless you were a bit of a programmer in 1980, I don’t think you can really appreciate how difficult it was to make something appear on screen that wasn’t formed with letters. The idea of computer graphics was fairly new and certainly didn’t filter down to the humble coding of the average user. Sure, there was Space Invaders; that had graphics. And Pong…

In fact, I think even the term ‘computer graphics’ drew a blank look from the majority of the population. What you be talking about, lad? Go do some colouring.

Ahem.

When it came to making a game that tried to immerse you into a world that wasn’t real, designers in those early days turned to the same tool that’s been used for centuries to provide an evocative image. They looked to books for inspiration.

Books, as I am sure you are aware, present a clear way to present anything in glorious imaginate-vision, using descriptive narrative to overcome all obstacles. A picture may be worth a thousand words, but conversely, a thousand words are worth a picture. Or something like that.

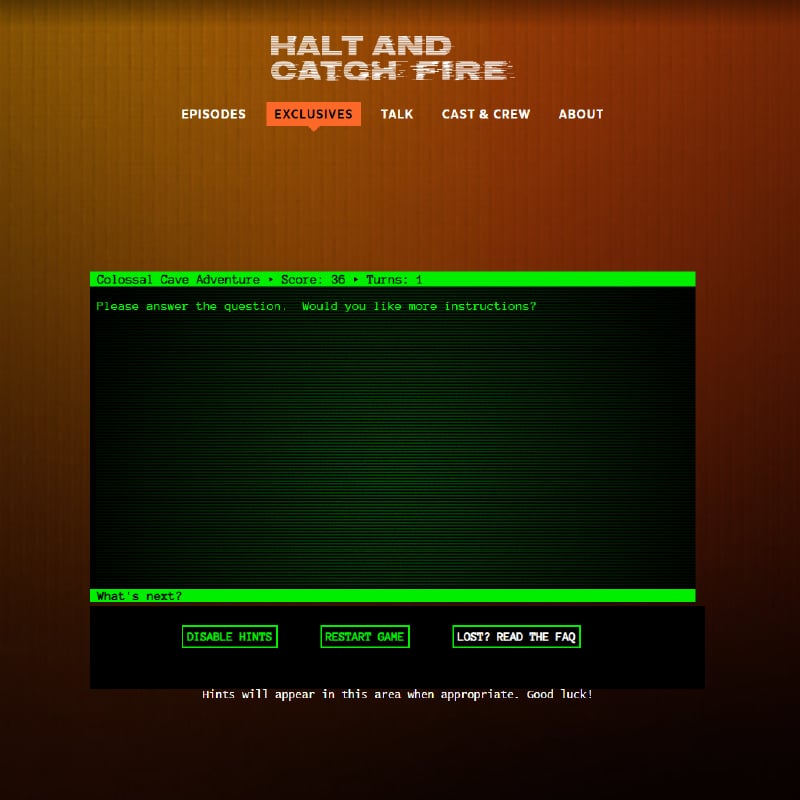

Let us take a look at the adventure game. It starts with something called Colossal Cave Adventure or, more simply, just Adventure.

Adventure was the very first piece of interactive fiction. Made in 1975 by Will Crowther, and written in a long-forgotten computer language known as Fortran, Adventure presented the player with a text description and waited for them to type back a command indicating what they’d like to do. Here’s an example of a description:

YOU ARE STANDING AT THE END OF A ROAD BEFORE A SMALL BRICK BUILDING. AROUND YOU IS A FOREST. A SMALL STREAM FLOWS OUT OF THE BUILDING AND DOWN A GULLY.

To which you might respond with:

GO SOUTH

Whereupon the game would tell you:

YOU ARE IN A VALLEY IN THE FOREST BESIDE A STREAM TUMBLING ALONG A ROCKY BED.

And so on, and so forth, as you adventure through this exciting new world.

It was the opening of a very important door.

Interactive Fiction

Books are linear. In a book, you don’t get any options or choices, you simply plod along learning the story in the way prescribed to you by the author. They are not really any more exciting than this article in that way.

But put you in the heart of the action, and all of a sudden, your book is something more meaningful. Now you are making the decisions that change the course of the story. Now, you are in control.

Once Adventure paved the way for the idea of interactive fiction, it wasn’t long before others joined the road, and along came Zork and its publisher Infocom.

Of all the companies to have made an impact in those early days of text adventure gaming, Infocom was by far, the most significant. Zork itself was a major hit, with players both then and now able to quote some of its more memorable lines. I still find myself worried that I may be eaten by a Grue every time it gets dark.

Beyond Zork itself, Infocom had success due to their implementation of an adaptable game engine, the Z-machine, which made their text-based games portable to a huge range of home computers. In the early 1980s, when no one could agree on what piece of technology to own, the ability to have your games quickly and efficiently ported onto every platform out there was a massive bonus. Infocom’s Z-machine meant that everyone could play Zork, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, or Planetfall no matter what system they owned – and that included people looking for a quick break from their spreadsheets on IBM desktops in offices everywhere.

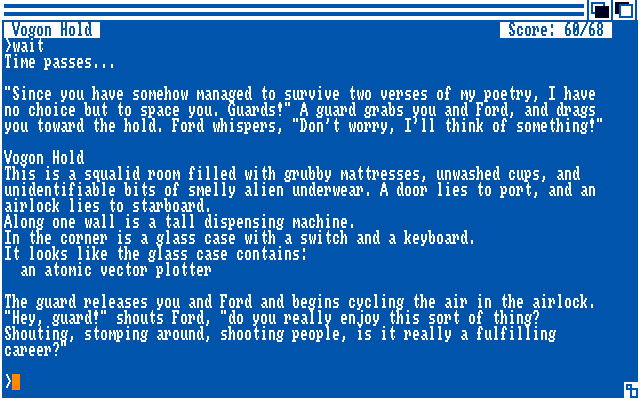

Licensing and Sex

There are two things guaranteed to sell; intellectual properties with a fanbase, and sex. Infocom was as aware of this as any other company looking to boost its profits. With two of their products covered the bases admirably. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, created with Douglas Adams on board, was one of Infocom’s greatest hits, following Arthur Dent’s story and his space travels with his best friend, Ford Prefect. Its association with Adams meant the script was tightly entwined with the original radio show and novel, and yet had enough unique moments to make it a must-own for any true Hitchhiker’s fan.

Then came the amusing, and somewhat lewd Leather Goddesses of Phobos, an adventure game ostensibly for adults, which allowed you to pick the gender of your character and offered a somewhat different storyline based on that basic choice. Here they had what everyone wanted – a little something to titillate.

As a young teenager at the time, I can admit that I spent far too long typing in everything I could think of into the parser line of Leather Goddesses… just hoping that I’d get it to say something outrageous. Though normally, it spat out nothing more than: “You can’t do that here.”

I beg to differ!

It’s All About the Parser

One of the things that held text adventures back (and made it very hard to simply try to code one at home), was the skill needed to develop a decent parser.

For those unaware of the term, a parser is the bit of software that takes the words you have written (the ‘input’) and makes some sense of it. After all, we’re talking about computers understanding the English language decades before assistants such as Alexa came into existence. Somehow, the computer had to understand what you wanted to do.

Text adventure controls weren’t as clean-cut as their arcade-game equivalents. In Space Invaders or Pacman, if you want to go left, you simply press left on the joystick, the computer receives a clear signal that you want to go left and the appropriate bit of program is run. Look – there’s your spaceship sliding left now! See you later!

But interacting with a novel? If I want to go left, should I type ‘go left’? Or should it be just ‘left’? What about ‘west’? Is west left? And what about if I’m particularly polite and write ‘go left, please’?

A good parser strips away the extraneous text (like the ‘please’) and works out exactly what you mean by your sentence, turning a string of words into a single clean signal, just like that joystick. Ah yes, he’d like to go left.

Or open the bag, examine the ground, check my inventory, or sing a little song.

And the best parsers would ask you questions to qualify your statement: ‘What would you like to sing?’ they’d ask.

Oh, thank you for asking. How about ‘Hot Cross Buns’?

One a penny, two a penny…

It was to their credit that Infocom not only had the multi-platform Z-machine, but they also had the best damned parser anyone had ever seen at the time. No wonder they were so successful.

Stepping Away from the Screen

With the boost in interest regarding the very idea of an interactive book, it wasn’t long before people tried to replicate the excitement of a text adventure game back onto paper. Of them all, it was Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone who were, undoubtedly, the kings of such a thing, with their 1982 super-success, The Warlock of Firetop Mountain.

Here the streams are definitely crossing, as the early work in role-playing games with Gygax and his Dungeons and Dragons heavily meets the computer-code of Adventure and Infocom’s growing stable of adventures.

The Warlock of Firetop Mountain was the first in a huge series of books grouped together as Fighting Fantasy. For each, you would read a passage and then be asked to make a decision. Will you: attack the goblin? (turn to 312) or run back through the door? (turn to 122).

Each choice meant you turned to a different page of the book and shaped the adventure yourself. Sure, the parser system was a little less in-depth than the one offered by Infocom, but you could take The Warlock of Firetop Mountain with you to school, and play during your lunch break. There was no way you were doing that with your Amstrad CPC464, let me tell you!

It wasn’t just the choice of pages that the Fighting Fantasy series offered, either. Taking their cues from Dungeons and Dragons, Messrs Livingstone and Jackson also included a dice-based combat system that, though very simple, added an extra dimension to their book series. This ensured it straddled the genres of book and game and meant Fighting Fantasy very reasonably belonged in that second category, as much as the first.

Are We Role Playing Yet?

With all these slightly different takes on interactive fiction, there was still a gap between the all-engaging atmosphere of Dungeons and Dragons and the growing number of similar games (Call of Cthulhu for fans of cosmic horror, Traveller for those looking for space opera, or Paranoia if you hate the idea of trust) and the text-based adventuring on offer. Importantly, for all the technical brilliance of Zork and its stablemates, they lacked the personal connection that makes true role-playing so absorbing.

That, and combat.

Remember, Dungeons and Dragons had grown out of wargaming and had combat at its core. Your character’s growth and development, often due to the combat, was something that kept you connected and coming back for more.

Infocom’s adventure games, those less-successful ones coming out from other publishers, and the traditional book-based Fighting Fantasy all lacked that sense of growth through experience.

In truth, a few stepping stones had been put down, but there was still a lot of work that needed to be done before anyone would call it a bridge.

Of course, we’re still way back in the early 1980s. There’s plenty of time for that development.

Zork in 2021

The question on everyone’s lips is, of course, can I get my hands on Adventure, those Infocom games, or even The Warlock of Firetop Mountain today?

And the answer is yes!

Frotz is a platform available for smartphones and desktop computers that offers a number of text adventures, including a version of Zork I.

TextAdventures.co.uk offers an online portal to thousands of similar treasures, and also includes the impressive facility to make your own text adventure game for others to enjoy.

Fighting Fantasy books have never really been out of print, and you can still obtain The Warlock of Firetop Mountain and friends from Amazon and other similar retailers.

As for Adventure, it’s been ported and copied so many times, and made available in so many ways. Here’s one that seems fairly faithful and true to the original.

Coming next…

Adding graphics to games required some innovation in the early days, but that didn’t stop a great many enthusiastic programmers and role-playing fans from trying. Moving on from text adventure games, I’ll be looking at the whole swathe of games that became collectively known as ‘rogue-likes’. You’ll die—a lot. See you there.